Soil Prep, Mulch, and Planning for April Planting: An Update to Getting Ready for the Growing Season

It's a crisp morning in the Appalachian Mountains here on Goldberry Grove as I wake up at 4:30 a.m. every weekday to check on the fledgling ducks and take my two dogs, Quasar and Duke, on their morning constitutional. This is a time shared between me and the morning air, before the sun has even risen. I am not yet bombarded by sound—the giggles and cries of my two-year-old—or the hard light of day. This is the time I dedicate as an almost meditative space for myself and my routine.

Each movement is practiced, reminiscent of my time in Hapkido and Taekwondo, performing a Poomsae (폼새) or Hyeong (형). I typically feed the animals first, let them out into the backyard, and then begin journaling and prioritizing the day's tasks. This includes spending either an hour writing or prepping social media content for Goldberry Grove.

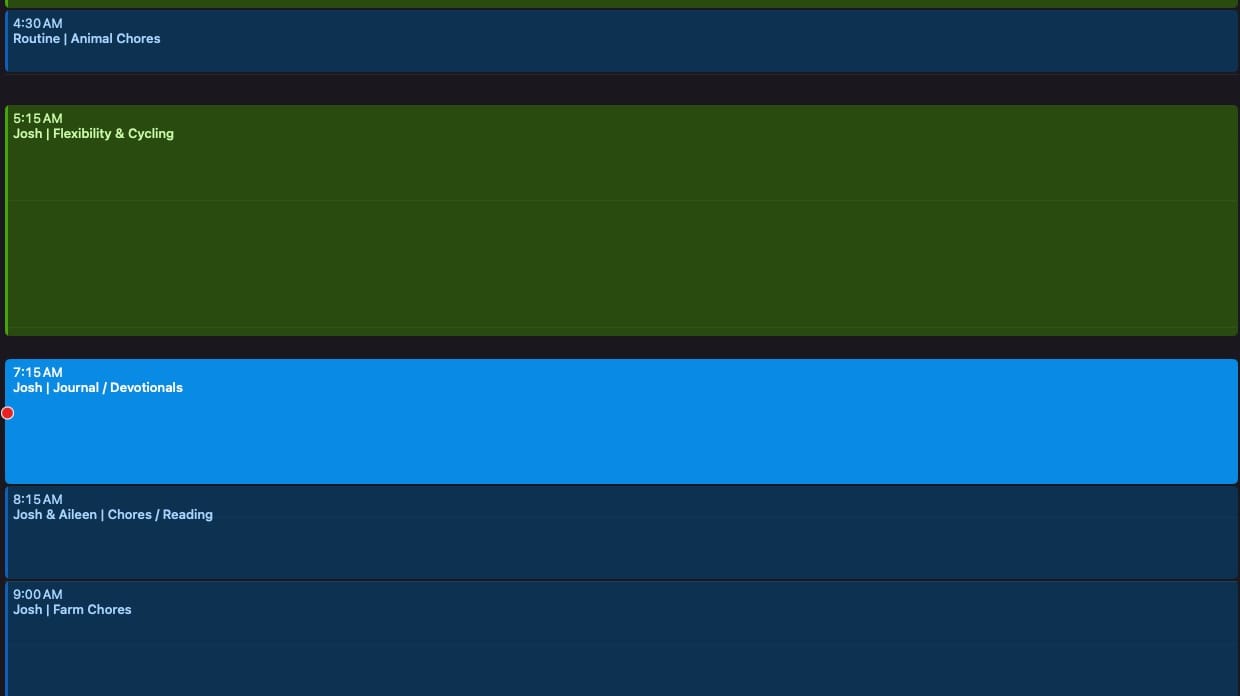

Then I spend about an hour stretching, cycling, or going to the gym, leaving some buffer time between tasks for smaller things like putting away dishes or picking up toddler toys. A typical routine for me looks like the following:

The hours from 9:00 to 11:00 a.m. are between me and the farm—doing what needs to be done. Now that we’ve got the seedlings heeled in before planting, I check to make sure they’re still healthy and well-covered in mulch. I make sure the buds are firm and that moisture is locked in around the root systems.

We’re currently awaiting the arrival of our new Kioti NS5310H, which is getting its third function installed as we speak. It’s coming equipped with the auger, box blade, subsoiler, grapple, and pallet fork we’ve been looking for.

Once it arrives, I’ll finally set the keylines I’ve marked a hundred times already in practice—this time permanently—then plow them in preparation for planting the 100 chestnut seedlings I’m now inspecting.

I head to the barn to let in the air and sun, waking up our three newest family members—ducks my wife named Ahiru (“duck” in Japanese and the name of the female lead in Princess Tutu), Pato (“duck” in Spanish—and Patito is just too cute to say), and Edna (like Edna Mode from The Incredibles).

I check on the three mushroom logs just outside, on the shadier side of the barn, making sure they’re still moist and protected from the extreme winds we regularly get on this property. Another task on the spring docket is establishing a black locust–dominant windbreak, interspersed with willow, American plum, and oak.

This particular morning, I’m getting ready to print the soil submission forms to send out six soil blocks—each representing just over an acre of our land—for lab analysis. I’ve also got a phone call scheduled to discuss farm-sitting arrangements for August, when we’ll be celebrating my wife’s 30th birthday. Another call is lined up to coordinate a compost delivery from Greenbrier County and to schedule a mulch drop-off in April.

Coordinating inputs like fungal-dominant compost, fall leaves, and wood chips has become a logistical headache. Much of what’s available locally hasn’t been produced with soil health in mind—contaminants like dewormers, herbicides, or poorly handled cattle bedding make it unreliable for immediate use. So, I’ll need to process most of what I acquire for at least another year before I’m comfortable using it. The compost I’m bringing in now is unbalanced and will need to be amended with straw and urea over the next year to reach a quality I’m happy with.

Once I’ve established a reliable system for sourcing inputs—gravel, wood chips, manure, and even leaves (which I can mostly gather from my own woods once I get a leaf vacuum)—we’ll begin producing our own JADAM fertilizers and fungal-dominant compost. These will be integrated with Korean Natural Farming methods and loosely guided by permaculture design principles.